The damage caused by the boat hook has obscured the injury and Freddie’s death will be declared an accident.

That doesn’t stop Tom from noticing, however, that Freddie has received a blow to the head which probably sent him into the river, and Freddie couldn’t swim. Henry uses a boat hook to lift him by the collar, but a mishap bruises his head.

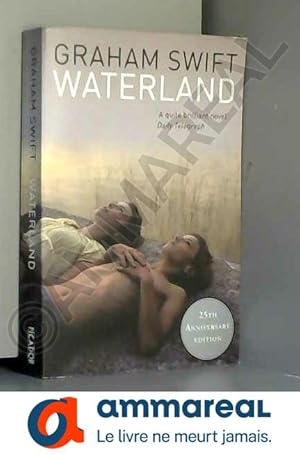

Extracting the body from the lock is difficult. He was the same age as Tom and had grown up less than a mile away in the sparsely populated fen country. What is more, the dead boy, Freddie Parr, is known to him and his sons. It should not be surprising, then, that in July 1943, Tom Crick’s father, Henry Crick, a lock keeper on the River Leem at the beginning of Graham Swift’s Waterland, should discover a body one morning, knocking and scrapping against the ironwork of Atkinson lock. Eco used it to describe narrative imperative, much like Chekhov’s gun: that narrative is inherently imbued with structural expectations.

As an old Asian proverb (even if its provenance is somewhat disputed) it suggests the importance of patience to overcome obstacles in life. There’s an old proverb, often attributed to Confucius or Sun Tzu (but definitely used by Umberto Eco in Reflections on the Name of the Rose) that if you sit by a river long enough you will see the body of an enemy float by.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)